You know how a song can get hopelessly stuck in your head? So can a promise to a stranger. Like a song, when the promise surfaces it has a way of circling back, nagging gently and sometimes causing irritation. Unlike a song, a promise stops nagging if it's kept. So the result of that simple moment when a stranger says, "Promise me you'll go to Utuado", and one answers without thinking, "I will," is that the promise becomes a song one can't get out of one's head. Until one keeps it.

So I had no choice. I had to return to Puerto Rico to go to Utuado.

Not that fulfilling my promise to visit Utuado was my only reason for returning. There are many other good reasons. To flee cold weather in the northeastern US for just a bit longer, to put a little money in the economy as a student at a Spanish language intensive and to explore how communities rebuild after extreme weather disasters are among them. Besides, the island needs people to visit - FEMA, of course - volunteer utility workers - church assistance groups - aid societies - maybe even Tesla to build those microgrids Elon Musk talked about in late September of 2017.

("Did Tesla come? Are they here?" I keep asking, but no one I've asked thinks they did.)

Tourists need to come here as well. Especially now. And, in spite of these blogs (or maybe because of them), I'm essentially a tourist on a bicycle (for the most part). I'm not a big spender, but for what it's worth, I believe my presence has some value.

In the not too distant future, when predictable stages of extreme weather post-disaster recovery are more widely familiar, those stages may look something like the following: 1) relief, joy and gratitude at having survived, 2) mourning who, and what, has been lost, 2) making sure oneself and one's community have what is needed to survive over the coming days and weeks, 3) restoring essential communication infrastructure and cleaning up enough debris so that transit is possible, 4) restoring basic services such as electrity, plumbing and drinking water, 5) returning to the tasks of daily life that help one to normalize - such as going to work, socializing and entertaining, and hopefully - 6) rebuilding in smart ways to meet the next extreme weather event with greater resiliency.

Most of Puerto Rico now seems focused on steps 4 and 5. An islander told me yesterday that he thinks 85% of the island now has power. That might be true on a per capita basis, but I doubt that it's true geographically. The more developed and populated coastal areas have had power for several months, but many of the more remote rural areas are still struggling.

I had the good fortune to share a meal in Quebradillas with Jeff and Virginia Toussaint, owners of The Flowing River Farm near the village of Orocovia, which is located in the center of the Island. Their farm recently joined WWOOF (World Wide Opportunities in Organic Farms, a "worldwide movement linking volunteers with organic farmers and growers to promote cultural and educational experiences based on trust and non-monetary exchange, thereby helping to build a sustainable, global community.") Jeff and Virginia are currently hosting farm worker volunteers even though they have no electricity and are using a large "life-straw" water filtering system to draw water from a local stream. They seemed weary when I talked to them, but perked up as they shared their vision to create a self sustaining, net-zero energy farm that could provide food for their family and the surrounding community. And as we spoke about climate activism, carbon pricing, energy independence, permaculture and our shared antipathy toward car dominant transportation systems (having very poor public transportation and few protected bike lanes, PR is completely car dependent) we re-energized one another to continue fighting for sustainable organic farming, smart infrastructure and clean energy solutions in spite of the obstacles.

There has been a lot in the news about the presence of poor drinking water since the hurricane. But Jeff and Virginia tell me that water hasn't been a consistently potable resource on parts of the island for years, so poor water is not a new phenomenon. On the coasts, it's been relatively easy to purchase bottled water for a few months. But when roads are out, obtaining bottled drinking water is difficult and can be cost prohibitive in poorer, more remote communities, so residents have been forced to drink substandard water or devise filtering systems, such as the Toussaints have.

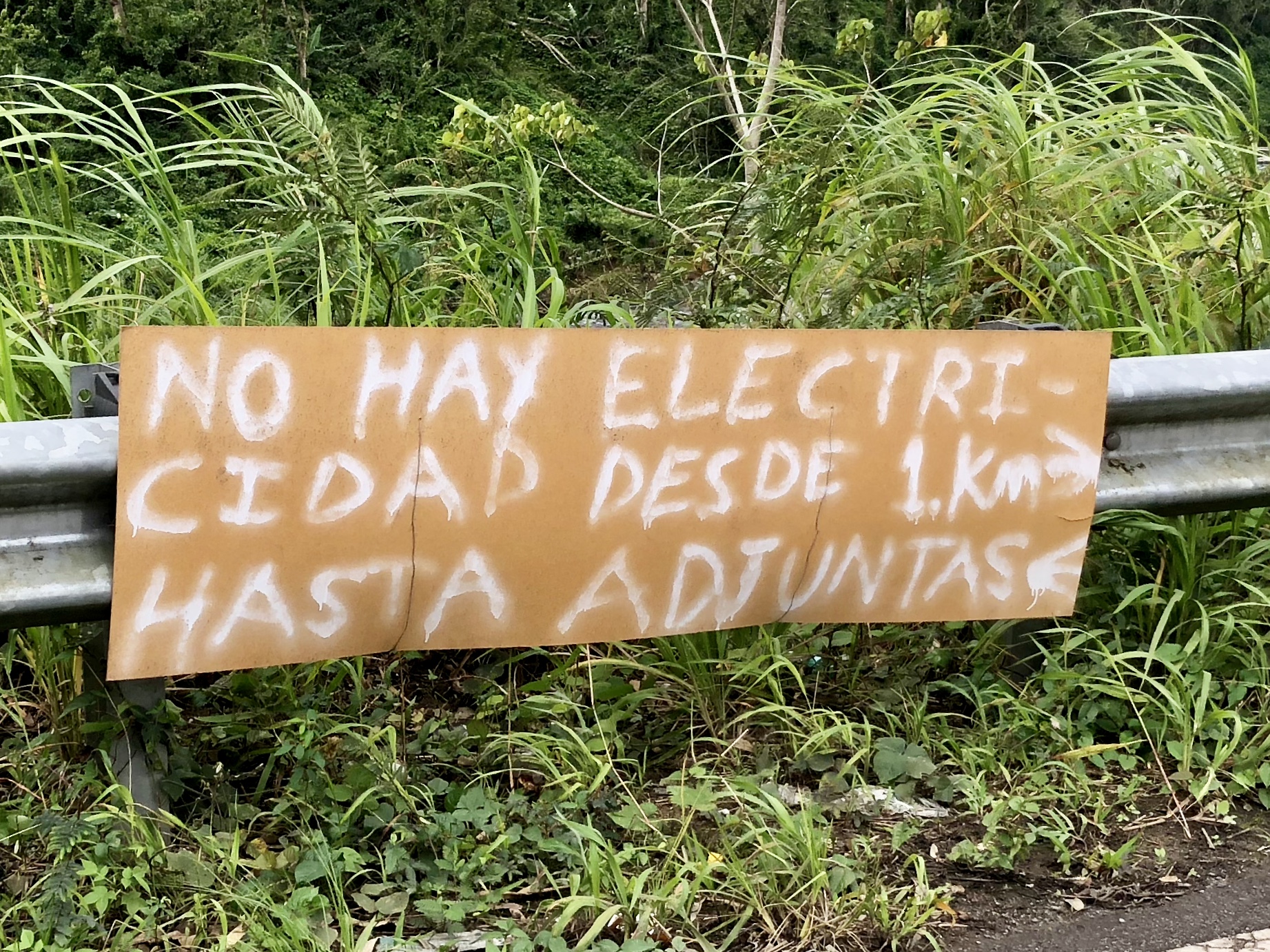

Just past Utuado, a reasonably large and spread out Pueblo south of Arecibo and north of Ponce, there is still no power between Rio Pellejas and Adjuntas in the communities accessible from Highway 123, a distance of about 25 kilometers. This area has received a lot of attention from the press, although that hasn't seemed to help PREPA get electricity beyond Utuado (which has had power since early February). PREPA is the Puerto Rican government run electric company, and you may have read that it will be sold later this year in an effort to privatize and modernize operations. Clearly, PREPA needs to be reimagined, so privatizing it may be helpful. It's essential that PR's electric grid becomes more responsive to the requirements of climate change. This is no mystery to Puerto Ricans. I encountered no resistance anywhere on the island to the notion that climate change will create more frequent and extreme hurricanes, greater ambient temperatures, increased precipitation, and storm surge flooding based on sea level rise. The average Puerto Rican seems to know what's coming.

I met Manolito, a Puerto Rican of Taino descent, as I walked through Rio Pellejas to inquire about electricity. There were new electrical cables on poles outside his house, but he and his neighbors were not connected. He didn't know if the cables were live, and he didn't seem too worried about it. His plumbing was fine, and that mattered much more to him. In fact, he mused that after five months, he had become accustomed to life without electricity. He'd be glad when it was back, but he wasn't that bothered by its absence.

From time to time I find myself reflecting on the reality that we humans have lived with electricity for only about a hundred years, and have enjoyed civilization without electricity for almost 10,000 of the 40,000 years our species has been around. Is its absence really such a crisis? Perhaps so when it comes to health care - modern medicine certainly cannot function without it. But in most other ways, I'm not so sure. (I do appreciate the irony of writing that statement while composing a blog on my cell phone.)

In spite of PREPA's overwhelming reconstruction challenge and their bureaucratic inefficiency, they have made some good choices. The government talks about establishing a portfolio standard with a goal of 30% renewables, which seems reasonable in an environment with an unlimited supply of wind and sunshine. Currently 13% of PREPA's full load is delivered through renewable sources. In 2012, PREPA contracted with Pattern Energy (headquartered in San Francisco, the company has 20 industrial sized wind and solar facilities all over the globe that generate more than 4000MW) to construct a wind farm slightly east of Ponce near the pueblo of Santa Isabel on the south coast. With 47 turbines, the Santa Isabel Wind Farm has a full capacity of 101 Megawatts, and is perfectly situation to take advantage of the constant and vigorous trade winds that blow from the east and southeast. Although the wind farm was built in 2012, the greatest capacity that PREPA has ever solicited has been 75MW (about 8% of PREPA's supply), which is what the farm was supplying to PREPA just before Hurricane Maria hit in September of 2017. There is another wind farm on the southeastern coast of PR near Naguabo called Punta Lima that was built and is run by Gestamp Wind, which had 13 turbines and a full capacity of 23MW. Unfortunately this farm was directly in the path of Maria and had to contend with winds that reached up to 200 mph. So, most of the turbines there were seriously destroyed by Maria, and the farm is not at all functional at this time. The Santa Isabel Wind Farm was also damaged, and some turbines are still being repaired. But its construction and fail safe technology allows it to survive 150 mph winds, and the blades can turn 180 degrees so that higher winds will be deflected and less damaging. At Santa Isabel, Maria's winds averaged 135 mph, with a few gusts that matched or exceeded 150 mph. As a result, about half of the turbines are currently online and the farm has a production capacity far greater than PREPA can currently utilize. At this time, PREPA is only taking 5MW. In spite of some ongoing repairs, the Santa Isabel Wind Farm will be able to supply at full capacity as soon as PREPA can absorb it.

I was impressed and delighted to learn that in this context the word "farm" has a double meaning. While fracking pads and oil wells are extraordinarily noisy and restrict terrain because of toxic exposure and protection from machinery, it is possible to grow crops directly underneath a wind turbine. The Santa Isabel Wind Farm is a "farm" in the truest sense of the word. Underneath its 3400+ acres are highly productive tomato fields, mango and papaya orchards, peppers, onions, eggplant, pineapple and approximately twenty other crops. The 800 acres of tomatoes can yield enough harvest in one day to supply the island for a week. The fields are shared with approximately 25 farmers who lease the land from the government at a beneficial rate, and also work closely with PR Farm Credit. In spite of Maria, the farms are fully functional now - which is very good news, considering that In the aftermath of Hurricane Maria, the New York Times reported that 80 percent of the crop value on the island — about $780 million — had been lost to the storm. Puerto Rico imports about 85% of its food, so the quick recovery of enterprises like this help lessen that dependency.

Behind my host Rueben Rivera of Pattern Energy and next to his truck, is a white trailer, which can be joined with other trailers to create a "train" pulled by a large tractor that can bring crops (tomatoes, in this case) to market.

While Rueben and I toured the farm, workers came in from the tomato fields for lunch. The Santa Isabel Wind Farm creates hundreds of sustainable jobs, primarily through agriculture. Interestingly, Ruben Rivera studied agronomy in college, even though he is now an operations manager for the wind farm. It was a pleasure to watch this capable man in an environment that aligns so closely to his values, way of life and skill set.

As we drove past the tomato fields we entered mango and papaya orchards. I cannot express how fulfilling it was to see how a clean source of energy could be paired with intensive food production. And, for skeptical readers, I want to make it clear that I took some time to get out of Ruben's truck and intentionally stand near a turbine while I listed to the white noise of the rotating blades. I have also stood near fracking pads, and I can assure you there is no suitable noise comparison. Anyone who complains about the noise of a wind turbine has never listened to an oil well or a fracking pad. Oil wells are irritating. Fracking pads are deafening. Wind turbines are neither.

These were my capable and warm hosts at the Santa Isabel Wind Farm, Carlos Roman and Ruben Rivera, respectively.

All good things must come to an end. These last photos were taken west of Quebradillas on the northwest coast, where in spite of obvious hurricane damage, the beaches are spectacular. I spent my last day biking along one of PR's few designated bike paths. And although I had to contend with a ferocious wind from the east, and dodge sand dunes altered by the hurricane, I was happy to be warm and sunbaked.

I recommend you go, if you can.